The plaintiff specializes in online sales of children's bicycles. In safeguarding its rights, the company has registered the design of these bicycles under Community Design. Through a multiple design registration, the company secures the rights for 10 new versions of its children's bicycles simultaneously under Community Design. Subsequently, when the defendant introduces a similar bicycle, legal proceedings ensue. Among the various claims, the plaintiff alleges infringement of its design rights, which in turn is contested by the defendant.

A design must possess novelty and individual character. The defendant states that the design lacks novelty, as elements of this design are already present in various existing bicycles. Essentially, the defendant's bicycles reproduce these elements, resulting in a lack of individual character.

According to the defendant, the community designs are thus invalid. Even If the plaintiff's designs should be valid, the defendant argues that its bicycle deviates sufficiently. The defendant argues that the plaintiff has sought protection for more or less similar designs in the multiple design registration. Apparently, the plaintiff believes that these designs differ enough to create a different overall impression. The defendant's bicycles deviate just as much, thus creating a different overall impression (the so-called doctrine of equivalents argument).

The question arises: are the plaintiff's bicycles valid designs despite comprising known aspects from various bicycles, or does the defendant's design exhibit sufficient deviation, thereby enabling the invocation of the doctrine of equivalents concerning the multiple design registration?

The court determines that designers of children's bicycles enjoy considerable freedom in their designs. Consequently, if another bicycle lacks significant distinctions, it will quickly evoke a similar overall impression for the informed user, thereby lacking individual character.

The comparison is drawn between the new design (the AMIGO bicycles from T.O.M.) and an older existing design (bicycle). To prove that a design is not new, you cannot, as Prijskiller (the defendant) asserts, mosaic together various elements. Therefore, as a defendant, you cannot argue that a design is not new because its characteristics are present in various different products (see also the judgment Karen Millen). If, as a designer, you combine different aspects from multiple designs for the first time into a new product, then this is simply a new and valid design. This is the case with the AMIGO bicycle. The design is upheld as valid.

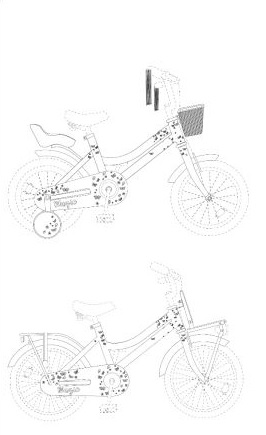

The AMIGO Magic bicycle features a unique tubular frame, rendering it novel. The bicycle is further distinguished by the name MAGIC, the chain guard design, and accessories such as a basket, handlebar streamers, and doll seat. Prijskiller contends that its frame shape differs (being thicker) and that the drawings are positioned differently. Additionally, Prijskiller highlights the distinct color scheme; however, TOM has registered the designs in line drawings, thus disregarding this element in the evaluation.

Nevertheless, several similarities are apparent. Both bicycles exhibit an almost identical pattern of butterflies and flowers, positioned nearly identically on the frame. Furthermore, the name MAGIC is depicted in the same font and placement on the chain guard. Consequently, this bicycle fails to evoke a different overall impression for the informed user. The designer's extensive creative freedom in designing children's bicycles means that the differences highlighted by Prijskiller are minor and inconspicuous.

Prijskiller's invocation of the doctrine of equivalents is likewise dismissed. The court opines that this case pertains to models concurrently deposited by T.O.M. This circumstance precludes the invocation of the "doctrine of equivalents" because, in compliance with the regulations regarding novelty, individual character, and the grace period, the various models cannot diminish each other's novelty or individual character, nor their scope of protection. In essence, in simultaneous (multiple) deposits, the "doctrine of equivalents" holds little significance.

Consequently, these 2Cycle Magic bicycles fail to impart a different overall impression for the informed user. The designer's extensive freedom in designing children's bicycles and the minor differences highlighted by Prijskiller render the infringement claim upheld.